During the pandemic year many faculty have been forced to create fully online classes in a Learning Management System, such as Canvas or Blackboard. It has been surprisingly difficult. Even those fluent in technologies like email and social media have been flummoxed by the difficulties of using the LMS as an online classroom. There are three main reasons why.

Got folders?

Learning Management Systems appear to be innocent shells into which teachers load “content”, but in reality they each have their own built-in pedagogy. This pedagogy is often archaic and is based on outdated norms of information organization. In the 1990s, LMSs imitated the folder-style structure of Mac and PC (Windows) operating systems. They were really just places to upload content items (usually Word files) and perhaps run a single discussion board (by 2005 or so).

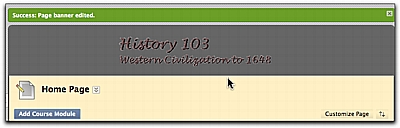

Surprisingly, even when LMSs added more and more features to enable greater interaction and activity, they retained the old structure. It is designed to present material by type: Pages, Lectures, Discussion, Grades, etc. You can see this in the way the menu is constructed.

Surprisingly, even when LMSs added more and more features to enable greater interaction and activity, they retained the old structure. It is designed to present material by type: Pages, Lectures, Discussion, Grades, etc. You can see this in the way the menu is constructed.

Presentation by type undermines the organizational integrity of the course. Most scholars think in terms of their field, and how best to present its habits of mind. As teachers, we think next in terms of wrapping elements together to encourage understanding. We do not think in terms of all the articles, all the lectures, all the exams, all the discussions.

Instead, we think in terms of weeks, or units, or modules. We section the learning, combining various elements to cover a particular subject. Separating those resources by type makes no sense when one is creating a pattern of learning.

One solution is to break this framework. If the LMS allows us to add, delete, or hide menu items,we can make new pages which link to the whole pattern of information. It may be possible, for example, to have the menu say Module 1, Module 2, etc., instead of Announcements, Syllabus, Pages, Discussion, Quizzes.

Even so, the system may force its own design. We may have a Module 1 page with all the links to activities, but when the student clicks on that activities, the breadcrumbs may show the folder name (“Quizzes”). Students can get lost following these.

Student-led what?

None of the major LMSs make it easy to implement constructivist or connectivist learning theory. Unlike twenty years ago, instructors may have studied and be trained in active learning teachniques, and have been using them in the classroom. When faced with the LMS, they find themselves stymied.

Created student-led or student-designed work is difficult. LMSs require teacher permissions to set up an assignment, quiz, content area, or discussion. Although some discussion forums allow students to begin topics, this feature must also be set by the instructor.

Some systems seems to be more adaptable, or at least expandable. In LMSs like Canvas, LTI’s (tools using the Learning Tools Interoperability standard) can be added to the system with varying levels of success. An example might be an improved discussion board, or Google Docs, or a group annotation app. Some integrate fairly well into the LMS, making them easy to access from inside the shell and pushing grades back into the system. But all require a bit of technical expertise to set up, and the integration is rarely seamless. Some, like Google Docs, may require students to have a separate Google account, while others need their own structural folder inside the LMS for all activity related to that app. This is particularly true of textbook publishers’ material, which often tries to integrate the publisher’s own textbook site with the LMS.

The solutions here take one of three directions: the internal approach, the LTI approach, or the textbook publisher approach.

Since students can be given control of discussion boards, the internal approach would include using them for different kinds of activity other than discussion: posting lists of websites, sharing resources, posting quotations from reading. The other folder areas (quizzes, pages, etc) can simply not be used.

The LTI approach would involve using more collaborative tools, like Google Docs or group annotation apps or pinboards as the main outside tool, with the instructor learning it well and monitoring it thoroughly.

The textbook publisher approach would be to ignore or hide everything possible in the LMS navigation and use the publisher’s folder as the main work area.

Fifteen papers due today!

Gone are the days when your class was the only online class students were taking. They are now enrolled in many classes within the same LMS at the same institution. In an effort to help them remember the deadlines for everything, the LMS aggregates all the information from all the courses into task lists, using a Calendar or To Do feature.

For example, a conditional release feature makes it possible to prevent a student performing Task B (a test) before they have done Task A (an assignment). Task A is designed to prepare the student for Task B, and ideally would be done within a short period of concentration. But on the student’s Calendar they see Task A, then Task 1 from another class, then Task iii from yet another class, before Task B. By the time they get to Task B, they have no idea what was learned in Task A. An example from three of may classes, running at the same time:

Perhaps you have designed a module to lead students through an introduction, then a short lecture, then a video, then a discussion, then a test. All of these will be disaggregated by due date and will appear in a jumble on the students’ Calendar. Wrapping elements for your class together to encourage deeper understanding becomes impossible.

In addition, by listing all the tasks from all the classes together, the Calendar or List “flattens” all the assignments. It becomes impossible to tell which tasks are more or less important to the student, to learning, or to the grade. They all look equivalent in the same font and size, even if one is a two-minute video and the other is a paper that would take several days.

Unfortunately, this problem may not be solvable. Few LMSs allow control over whether or not to show calendars and lists to students. Because permissions for such features run above the individual course level, instructors usually have no access to any methods that would change the LMS behavior.

The bottom line

Creative pedagogy can work within the limitations of the LMS, but it is not easy to implement. Systems are designed to systematize, and the LMS is designed to create cookie-cutter classes based on outmoded structures rather than to promote innovative approaches. Thus for many of us, understanding its design is essential to adapting, subverting, or acquiescing to its suckiness.

But that’s not the real challenge – it’s the material. For each chapter, there is a long list of resources: document activities, image activities, map activities, “closer look” features. Since each of these has at least one question attached (I assume that’s the “activity” – there’s nothing else active here), I assumed these were multiple choice questions, for automatic grading. Turns out most of them are “essay” questions, all of low quality (i.e. “what is x talking about in this document?”), that I would have to grade. I’ve assigned over a dozen for each chapter. Besides, the whole idea of the experiment was to be using their pedagogy as much as possible instead of mine.

But that’s not the real challenge – it’s the material. For each chapter, there is a long list of resources: document activities, image activities, map activities, “closer look” features. Since each of these has at least one question attached (I assume that’s the “activity” – there’s nothing else active here), I assumed these were multiple choice questions, for automatic grading. Turns out most of them are “essay” questions, all of low quality (i.e. “what is x talking about in this document?”), that I would have to grade. I’ve assigned over a dozen for each chapter. Besides, the whole idea of the experiment was to be using their pedagogy as much as possible instead of mine. Some don’t even have a date! They let you into just enough code that I can kind of correct some of these by adding words to the title. But there are audio files with no lyrics or transcripts. And, worst of all, the primary source video clips (Edison’s footage of Annie Oakley, footage of the Rough Riders) are in low resolution and look terrible. I could find better quality of the same footage using Internet Archive. There are also typographical errors in the transcript and in the titles and descriptions of the sources.

Some don’t even have a date! They let you into just enough code that I can kind of correct some of these by adding words to the title. But there are audio files with no lyrics or transcripts. And, worst of all, the primary source video clips (Edison’s footage of Annie Oakley, footage of the Rough Riders) are in low resolution and look terrible. I could find better quality of the same footage using Internet Archive. There are also typographical errors in the transcript and in the titles and descriptions of the sources.

My college is upgrading to Balrog, I mean Blackboard, 9. I have been invited to pilot it for fall. So perhaps, just perhaps, I should run the class there. I’d learn about Bb9 so I can help faculty, and I’d see how much web 2.0-my I can plug into it.

My college is upgrading to Balrog, I mean Blackboard, 9. I have been invited to pilot it for fall. So perhaps, just perhaps, I should run the class there. I’d learn about Bb9 so I can help faculty, and I’d see how much web 2.0-my I can plug into it.