One of my current projects is a chapter on H. G. Wells and education, which I’m writing for the Oxford Handbook on H. G. Wells. I have been struggling a bit with this. Each chapter of these Handbooks features an expert on the subject making an argument about their topic. My argument from the start has been pretty clear: that whatever else Wells might say he is doing, he is always trying to educate people.

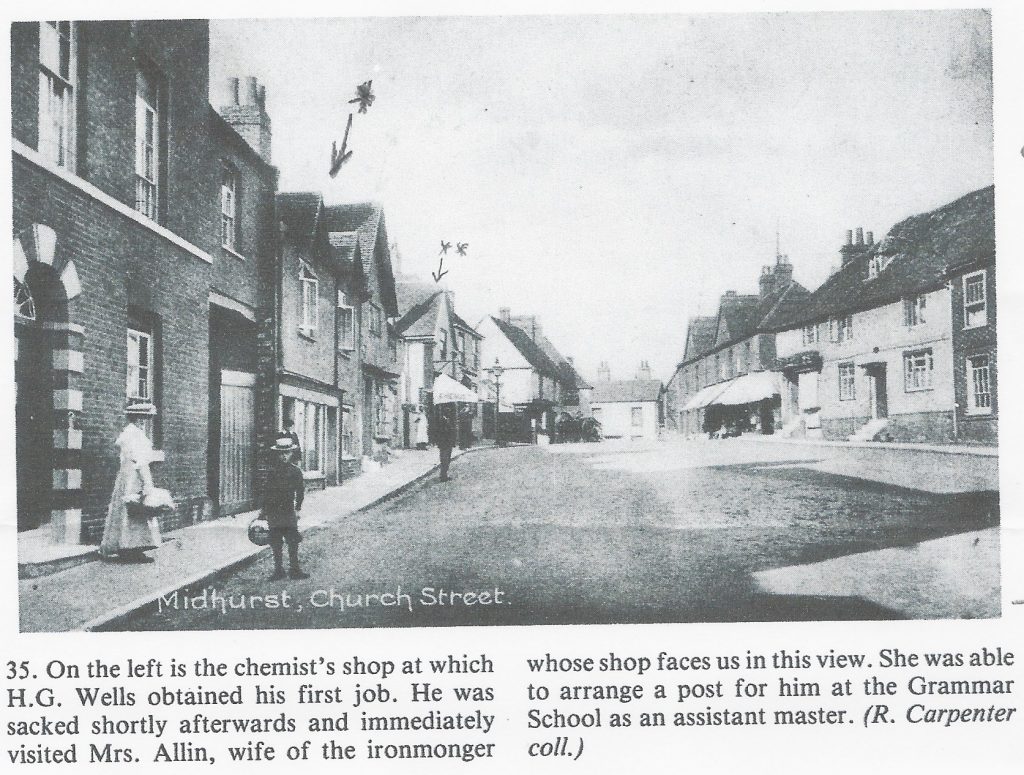

My expertise in this area is very much focused on the years of Wells’ life before he wrote The Time Machine at age 29. His work prior to that was very much focused on education, first his own and then the pupils he taught as a pupil-teacher, schoolmaster, and tutor. He wrote extensively on education, drawing on his own experiences as a student, first in a dame school and then a commercial academy, and then his job as a teacher. I have recently republished 81 of the articles he wrote on science teaching, pulling them together in a book for the first time. However, since I’m writing the only chapter on education for the Handbook, I need to extend my coverage from The Time Machine in 1895 forward to his death in 1946.

My expertise in this area is very much focused on the years of Wells’ life before he wrote The Time Machine at age 29. His work prior to that was very much focused on education, first his own and then the pupils he taught as a pupil-teacher, schoolmaster, and tutor. He wrote extensively on education, drawing on his own experiences as a student, first in a dame school and then a commercial academy, and then his job as a teacher. I have recently republished 81 of the articles he wrote on science teaching, pulling them together in a book for the first time. However, since I’m writing the only chapter on education for the Handbook, I need to extend my coverage from The Time Machine in 1895 forward to his death in 1946.

Thus I need not only an argument, but explanations when Wells’ work shifts, or seems to shift, to the other topics he wrote about. In addition to the scientific romances of his earlier career, he published books on science (his first published book was a biology text-book), sociology, history, peace, war, politics, and many other topics besides. He wrote novels and short stories. He gave speeches and wrote articles and columns for journals and magazines. He was ridiculously prolific, and not all of it was directly about education. I need more than an argument — I need an approach.

So I have been thinking. A lot. Instead of writing, which makes me feel like I’m procrastinating. People often ask me: why Wells? I have tried in vain to recall when I first discovered that he had tutored biology by post as a young man. As someone who had specialized in teaching online for over two decades, I felt an immediate kinship to a man who carried examination books with him everywhere, grading in coffee shops and omnibuses before sending the corrected papers back to distant students. I honestly don’t think I’d read any of his books or stories before I started researching his experiences at the University Correspondence College. I was a distance educator relating to another distance educator over a gap of 120 years.

As I conducted my research into his writings between 1897 and 1946, I was starting to lose that focus, getting tangled up in the polemics which became his mode of communication in his later years. It seemed as though he began with science and teaching journalism (he always considered himself a journalist of sorts), then wrote novels for fun and profit, then more polemic works from a particularly Wellsian socialist point of view, ending with a book whose title I just love: Mind at the End of Its Tether. Many of his later writings were done in frustration at humanity’s inability to conduct its affairs in a rational manner.

Although there is much overlap in his works before and after World War I, that conflict provides a likely breaking point between his earlier and later works. Even when they were frightening, pre-war scientific romances such as War of the Worlds and The Island of Dr Moreau retained their optimism in the form of a protagonist horrified at what was happening. His “conversation novels” and what I consider more feminist works (especially Ann Veronica) also have a strain of optimism. But after the war, the novels become more and more direct in their criticism of humanity. Wells seems to have taken the senselessness and mass deaths of the Great War as a sign of the end of civilization. He was not alone in this, of course. But it’s almost as if Wells took it personally, and his work becomes more and more polemical, diagnosing society’s ills and demanding remedies.

Although there is much overlap in his works before and after World War I, that conflict provides a likely breaking point between his earlier and later works. Even when they were frightening, pre-war scientific romances such as War of the Worlds and The Island of Dr Moreau retained their optimism in the form of a protagonist horrified at what was happening. His “conversation novels” and what I consider more feminist works (especially Ann Veronica) also have a strain of optimism. But after the war, the novels become more and more direct in their criticism of humanity. Wells seems to have taken the senselessness and mass deaths of the Great War as a sign of the end of civilization. He was not alone in this, of course. But it’s almost as if Wells took it personally, and his work becomes more and more polemical, diagnosing society’s ills and demanding remedies.

Mr. Wells and I have a few things in common, not the least of which is frustration when teaching students. His teaching years occurred when science was new to the university curriculum; mine during the first decades of the internet. We both blamed poor teaching methodology for why students seemed to learn so little, and were in ongoing conflict against curricular stagnation. We both developed new techniques to teach at a distance (although I never created anything as visceral as Wells’ kitchen-table biology lab). If the Great War was his bending point, the election of our 45th president in 2016 was mine. From those points it became difficult to believe that we, as teachers, had made any difference at all. When Wells met his Waterloo, he was 48. I was 53. We had both seen a lot, and been teaching long enough to have developed it as an art. If we’d been making any difference, how could humanity have gone so wrong?

Wells’ The Outline of History (1920) and A Short History of the World (1922) were published right after WWI. It seems clear to me now they were an attempt to teach people about the past so humanity could avoid mistakes. I’ve been teaching history since 1989. For both of us, education has always been the answer to everything. If things go wrong, and people do awful things, it’s because they just aren’t educated enough. They literally don’t know any better.

Wells’ The Outline of History (1920) and A Short History of the World (1922) were published right after WWI. It seems clear to me now they were an attempt to teach people about the past so humanity could avoid mistakes. I’ve been teaching history since 1989. For both of us, education has always been the answer to everything. If things go wrong, and people do awful things, it’s because they just aren’t educated enough. They literally don’t know any better.

It’s the connection between my experience and that of Wells that started me on my Wellsian quest, and it will be that connection that guides this chapter. The fear is that ones efforts as a teacher are useless, and if that’s true there is a possibility that mankind might be ineducable. That is far scarier than Martians blasting the planet or men becoming invisible to commit crimes. When his book War in the Air was republished in 1941, during the Second World War, Wells wrote in the preface that he wanted his epitaph to be “I told you so. You damned fools.” While this has been interpreted as relating to his many prophecies about technology, I think it is more about education.

My expertise in this area is very much focused on the years of Wells’ life before he wrote The Time Machine at age 29. His work prior to that was very much focused on education, first his own and then the pupils he taught as a pupil-teacher, schoolmaster, and tutor. He wrote extensively on education, drawing on his own experiences as a student, first in a dame school and then a commercial academy, and then his job as a teacher. I have recently republished 81 of the articles he wrote on science teaching, pulling them together

My expertise in this area is very much focused on the years of Wells’ life before he wrote The Time Machine at age 29. His work prior to that was very much focused on education, first his own and then the pupils he taught as a pupil-teacher, schoolmaster, and tutor. He wrote extensively on education, drawing on his own experiences as a student, first in a dame school and then a commercial academy, and then his job as a teacher. I have recently republished 81 of the articles he wrote on science teaching, pulling them together  Although there is much overlap in his works before and after World War I, that conflict provides a likely breaking point between his earlier and later works. Even when they were frightening, pre-war scientific romances such as War of the Worlds and The Island of Dr Moreau retained their optimism in the form of a protagonist horrified at what was happening. His “conversation novels” and what I consider more feminist works (especially Ann Veronica) also have a strain of optimism. But after the war, the novels become more and more direct in their criticism of humanity. Wells seems to have taken the senselessness and mass deaths of the Great War as a sign of the end of civilization. He was not alone in this, of course. But it’s almost as if Wells took it personally, and his work becomes more and more polemical, diagnosing society’s ills and demanding remedies.

Although there is much overlap in his works before and after World War I, that conflict provides a likely breaking point between his earlier and later works. Even when they were frightening, pre-war scientific romances such as War of the Worlds and The Island of Dr Moreau retained their optimism in the form of a protagonist horrified at what was happening. His “conversation novels” and what I consider more feminist works (especially Ann Veronica) also have a strain of optimism. But after the war, the novels become more and more direct in their criticism of humanity. Wells seems to have taken the senselessness and mass deaths of the Great War as a sign of the end of civilization. He was not alone in this, of course. But it’s almost as if Wells took it personally, and his work becomes more and more polemical, diagnosing society’s ills and demanding remedies. Wells’ The Outline of History (1920) and A Short History of the World (1922) were published right after WWI. It seems clear to me now they were an attempt to teach people about the past so humanity could avoid mistakes. I’ve been teaching history since 1989. For both of us, education has always been the answer to everything. If things go wrong, and people do awful things, it’s because they just aren’t educated enough. They literally don’t know any better.

Wells’ The Outline of History (1920) and A Short History of the World (1922) were published right after WWI. It seems clear to me now they were an attempt to teach people about the past so humanity could avoid mistakes. I’ve been teaching history since 1989. For both of us, education has always been the answer to everything. If things go wrong, and people do awful things, it’s because they just aren’t educated enough. They literally don’t know any better. This morning I had the pleasure of presenting to the H. G. Wells Society for their conference “Experiments in (Auto)biography: H.G. Wells and Life-Writing”. I was asked to talk about the background to my novel and my recent collection of his science teaching writings. It was fun!

This morning I had the pleasure of presenting to the H. G. Wells Society for their conference “Experiments in (Auto)biography: H.G. Wells and Life-Writing”. I was asked to talk about the background to my novel and my recent collection of his science teaching writings. It was fun!