I came across (and purchased immediately) a Wells book I hadn’t seen before: his Pocket History of the World.

It was published in 1941, so two years after the war had begun and five years before Wells died. He promises in the introduction that it is not a condensation of his Outline of History, but it does seem to be a revised version of his Short History of the World, with one obvious exception: time.

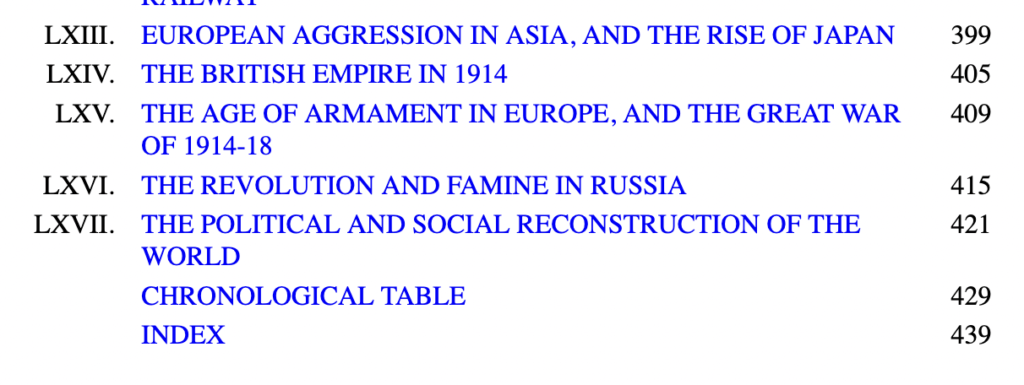

Here is the end of the contents of A Short History of the World:

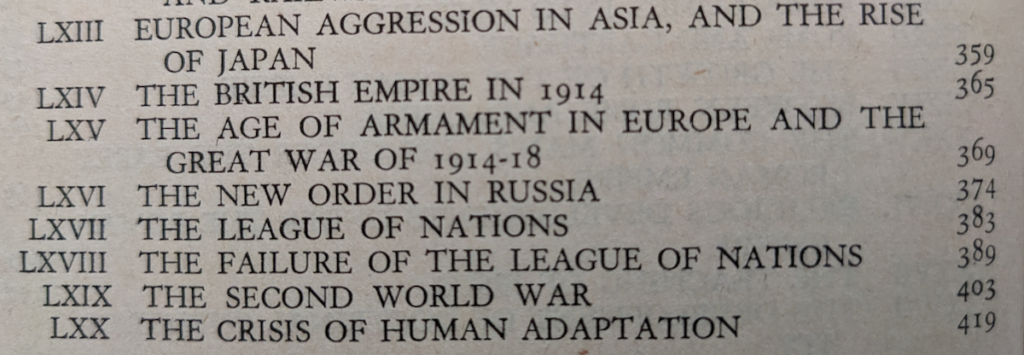

Because it was written in 1922, it ends there. But the Pocket History (like my own history classes) must revise the end:

This does seem to be new material, and it comes out the same length as the old in terms of page count, because so many images have been removed. The Second World War, already called that in 1941, is happening as he’s publishing. That section ends:

The criticism of British military effort would be amusing if so many people hadn’t died during the failure. And his note of hope is interesting, and prescient (Wells is always prescient) since the Allies will ultimately win. But the interesting part is the final chapter, “The Crisis of Human Adaptation”, both in its evolutionary tone and its content. The beginning seems to be original to this pocket edition, or at least I cannot find it anywhere else:

It is scarcely an exaggeration to say that at present mankind as a species is demented and that nothing is so urgent upon us as the recovery of mental self-control. We call an individual insane if his ruling ideas are so much out of adjustment to his circumstances that he is in danger to himself and others. This definition of insanity seems to cover the entire human species at the present time, and it is no figure of speech but a plain statement of fact, that man has to “pull his mind together” or perish.

This is the voice of Wells in the 1940s, to my mind. He goes on to explain that in the book is traced the steady growth of humanity, especially in terms of inventions and science, but he asks the reader to review what he’s said about economics, where “adventurers and speculators” continue to hold sway. Until a “vast and systematic collective mental effort” gets money organized:

…quite apart from the monstrous dangers of our insane international life, we suffer an insecurity that may some day seem incredible, in our blundering economic circumstances. No common many nowadays is safe anywhere from impoverishment and want.

But what’s interesting is what isn’t there after these paragraphs–a revision of his thought based on a second world war. Instead, following his statement about economics, he merely repeats much of the last chapter of his Short History of the World, which pushed for a world democratic order, derided the League of Nations and the “patched-up system of conferences”, and proclaimed that man was still adolescent, with “undisciplined strength” but not enough knowledge. He concludes with mankind’s enjoyment in nature and artistic creations as hopeful signs (again repeated from the 1922 Short History). But as the war progresses I see his view as less and less optimistic, until we get to his final book (Mind at the End of Its Tether).

Also in 1941, Wells wrote a preface to his 1908 novel War in the Air, at the end of which he wrote:

Is there anything to add to that preface now? Nothing except my epitaph. That, when the time comes, will manifestly have to be: “I told you so. You damned fools.” (The italics are mine.)

I believe his patience had run out.