Your course is designed by an instructional designer, and your assessments are graded by computer or by someone in India. The question is — are you still the teacher?

As a professor, I have been designing, delivering, and agonizing over my own classes for 23 years. This didn’t change when I began teaching online 15 years ago. I found the knowledge I needed to create my classes and I did it. I have never used an instructional designer, a design team, a TA, a grader, or anyone who was paid to help me with creating my classes. My knowledge of pedagogy has come from readings and classes I did on my own, and the wonderful people of many professions in my network, many of them online professors and teachers also.

I already argued back in 2011 why communities for online instructors must be led by faculty. Instructional designers, I said, are caught in between the standardization promoted by the institution’s technology decisions and the needs of faculty who want to help their students. I’ve argued against the use of computerized grading. But perhaps the overall message is being missed.

It’s about the role of the professor, especially at a community college.

In addition to teaching, I read a lot of work by PhDs in instructional design and technology, and I keep up with the “innovations” emerging in the proto-commercial educational world. In an exchange awhile back, my Twitter colleague Jennifer Dalby, an instructional designer, made an analogy between teaching a course and a symphony. One person wouldn’t compose, perform and conduct a symphony, so why would the same person both design and teach an online class?

So I thought about this and realized, no, it isn’t like a symphony (although the likes of Beethoven and Mozart did compose, perform and conduct).

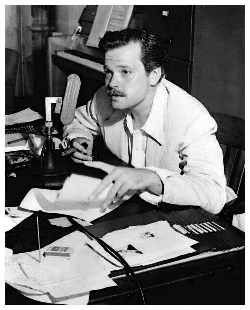

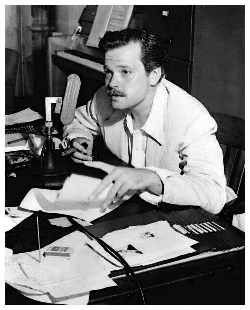

It’s like making a movie. And I want to be Orson Welles – writer, director, actor. It’s my class. I write it when I create the syllabus and collect the materials. I direct it when I teach and assist students. I act when I’m lecturing or presenting.

But now that we’ve professionalized “instructional design” (and other aspects of education that used to be considered support rather than primary functions), I feel there’s a movement afoot to have me just act. Someone else has a degree that says they are more qualified than I am to design my class, in collaboration with me as the “content expert”. They want to do the writing, create the storyboard, tell me what the “best practices” are.

They are trying to turn me into Leonardo DiCaprio instead of Orson Welles. They want me to profess, to perform, to present, and that’s it. (They’ll record that, so my students can view it later. Others can set up a “course structure” around my performances.)

Well…that’s not OK. As a professor, I do not simply profess – I teach. All the decisions involved in teaching should be made by me. It’s not that I don’t understand the limitations (transferrability concerns, student learning outcomes), but beyond those limits the decisions about which materials to use, and how to use them, and what to have students do, and how to assess that, etc. etc. etc. should be mine. Doing those tasks are teaching.

At community colleges, we have the ideal teaching environment. It’s the one place between the restrictions of the K-12 curriculum dictated by states, and the research-based non-teaching focus of universities. At the university, I suppose some faculty might beg for instructional designers, especially if teaching isn’t what they want to be doing. At community colleges, we have no such pressures – the main job we have is teaching. This shouldn’t change just because we teach online.

There are a couple of risks in letting things continue the way they are heading:

There are a couple of risks in letting things continue the way they are heading:

1. Our profession will be de-professionalized. This happens as parts of our job become other professions. It’s like outsourcing key parts of your job. What will happen if they offer a PhD in Assessment? in Attendance? in Essay Assignment Design? Will we all become Leonardo, adding our special touch to the work of others, instead of creating our own?

2. We help perpetuate the myth that teaching online is too hard for ordinary teachers. It isn’t 1998 anymore. It no longer takes deep technical knowledge to teach online. Instead it takes the desire, a lot of energy and some self-acquired knowledge. But if we are all told that we need instructional designers and educational technologists to help us, from baby steps to final course, we will become totally dependent and our creativity will be stifled.

3. The courses could become cookie-cutter. The LMS already encourages this. If everyone chooses from the same set of instructional design “best practices” recommendations, variety will be lessened. As individuality succumbs to standardization, students will become more accustomed to the same platforms and approaches, limiting their thinking and their learning.

(And yes, if you’re thinking gosh, this sounds like an anti-MOOC argument, it could be that too…)

Welles demanded, and got, full artistic control of his work. He tried new ideas, acted and produced, worked in different mediums. No, there aren’t many like Orson Welles (or John Huston or Woody Allen or Robert Redford). But striving to attain that level of creative control should be expected, supported, and applauded in community college education. We should take back our classes and teach them.

I love it. I’m the kid who sat on the floor reading the encyclopedia. I’m the student who got thrown out of the library when it closed. I’m the one looking up studies on the internet. I love content. All content. The expression of human knowledge, going back for centuries. Give it to me. In books, online, in text, on video. I want it all.

I love it. I’m the kid who sat on the floor reading the encyclopedia. I’m the student who got thrown out of the library when it closed. I’m the one looking up studies on the internet. I love content. All content. The expression of human knowledge, going back for centuries. Give it to me. In books, online, in text, on video. I want it all.

This year, our Program for Online Teaching leadership for the

This year, our Program for Online Teaching leadership for the

MOOCs are not all created equal. We can’t keep treating them monolithically.

MOOCs are not all created equal. We can’t keep treating them monolithically.

There are a couple of risks in letting things continue the way they are heading:

There are a couple of risks in letting things continue the way they are heading: