The word “lecture” conjures an idealized image of students listening attentively as a professor relays knowledge. Almost all of the lectures I enjoyed at university were in this format, and when I began teaching I lectured this way too.

With this year’s quick and unexpected transition to online teaching, many professors assumed that online lecture meant reproducing what they do in class. Zoom.com was grateful for this assumption, even as they struggled to accommodate the massive numbers holding live lectures. Almost immediately, however, there were complaints and problems.

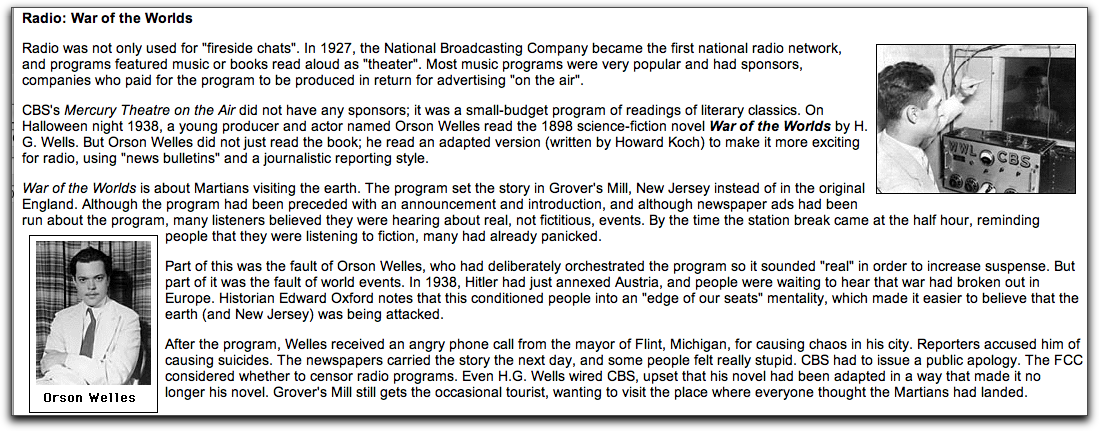

Professors whined that students weren’t paying attention, or didn’t want to turn on their cameras. They couldn’t see the facial expressions and body language indicating comprehension (or lack thereof). Students complained about boring, wandering lectures, and they felt exposed. You can’t sit at the back in an online classroom, and they didn’t want thirty strangers to see the trailer they lived in. Many decided they would watch the recording instead.

The problem? Zoom provided the platform, but the pedagogy was still based in the classroom. This worked better for some professors than others. At our college, they let us choose before this fall whether we wanted our classes scheduled and in Zoom, or “online only” (meaning asynchronous, with no live meetings), or a mix. Many professors regretted their choice. Those in Zoom wished they hadn’t, and those who chose asynchronous were sorry they’d done that.

For two decades, I’ve been pushing the idea that the technology should follow the pedagogy. Your preferred teaching method should dominate. In the rush, there had been no connection between a professor’s pedagogy and their choice of format.

So, assuming you lecture, what kind of lecturer are you?

Interactive lecturers count on student participation. They ask questions during lecture, or survey the mood, or set tasks for students during the lecture.

Interactive lecturers count on student participation. They ask questions during lecture, or survey the mood, or set tasks for students during the lecture.

Interactive lecturers should consider live (synchronous) lecturing in Zoom or another webconferencing program. The live approach online, however, works best for the simple lecture, on one topic. Shortening lecture time by about 2/3 is also a good idea for live session lectures, but they can be immediately followed by breakout room activity.

Traditional lecturers are those who lecture to an audience, and don’t expect, need, or want the lecture to be interactive. They relay a lot of information, framed by their own interpretation from their professional experience.

Traditional lecturers should record these lectures, and students can view them in an asynchronous way. Students particularly appreciate recorded lectures when the topic is complex, so they can go back and review without being on the spot.

Online lecturers, long ago, were all using dial-up modems and there wasn’t much bandwidth. A lecture quickly became a typed out version of ones lecture notes. As bandwidth expanded, these written lectures could be enhanced with images, then audio, then video. Written lectures can be more like reading, or they can be multi-media experiences, but they’re based on the web page or blog. They may include recorded mini-lectures. Like traditional lectures, they tend to be asynchronous.

So, planning to offer a 90-minute lecture on the historiography of the fall of ancient Rome? Go ahead, but considering recording it with images or video clips rather than doing it live. Want to lecture on solving a quadratic equation, using a whiteboard and asking students to help as you go? Consider a live lecture. Already wrote a great article that covers everything that would be in this week’s lecture? Record your voice reading it, and add some pictures or video clips.

But we don’t all have a choice. Have you been told you have to fill 75 minutes of scheduled class time? Consider creating interactive lectures and activities that require working together. Or have students view a recorded lecture, then come to the synchronous class to work out problems or just do their homework together. I would consider this a flipped online classroom, a model that understands that absorbing information may be best done on ones own but applying it should be done together.

So as we approach spring, let’s consider.

So last term, given all these limitations and the execrable quality of open access textbooks in History, I asked the department for some printing funds. Since I teach so many classes online, I do not use much printing money each term. With this money I was able to have printed enough textbooks for the whole class (much easier in a time of declining enrollments). I did it half size and spiral bound, making a rather attractive if thick booklet.

So last term, given all these limitations and the execrable quality of open access textbooks in History, I asked the department for some printing funds. Since I teach so many classes online, I do not use much printing money each term. With this money I was able to have printed enough textbooks for the whole class (much easier in a time of declining enrollments). I did it half size and spiral bound, making a rather attractive if thick booklet.