The advantage of teaching so many classes online is that I see patterns in student messages that lead me into larger issues. This one is HUGE. It’s not just about Canvas. It’s about the decline of Western education as we know it.

I stopped using Modules last term, because they “flattened” the elements of my class, making it appear as though each were of equal worth. Modules also forced students along a linear path of that week’s work.

I instead chose to keep my weekly pages, which list the things we do each week and when they’re due. I use bold for the higher-stakes assignments. Canvas automatically puts my due dates on the Calendar, and thus populates the students’ To-Do and Upcoming lists, which appear on the main (Home) page.

Over the years, more and more classes have switched to Canvas, so the average full-time student at MiraCosta would have four classes in a term. What the Canvas Calendar does is acts like any other calendar — it lists the tasks for each day or each week or each month. On the student Canvas app, it shows the To-Do list for each week from all their classes.

Sound convenient? It is convenient in the same way that bottled water is convenient, and that credit cards are convenient. It undermines traditional relationships globally, and creates a sea change.

Yes, I probably sound crazy saying that the Canvas Calendar represents the decline of Western education as we know it. But bear with me.

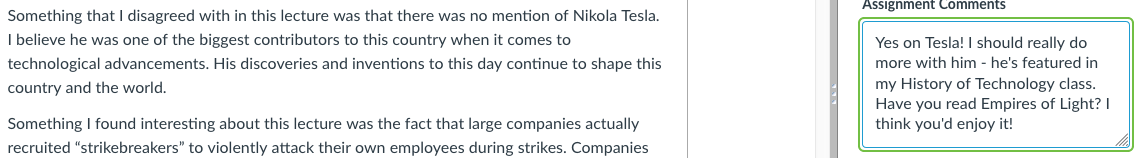

This week, the first week of class, I have had an unusual number of students message me saying they missed the assignment because they didn’t “see” it. By probing this, I’ve discovered that they mean it isn’t appearing in the To-Do list. This is regardless of the fact that I did check to the box to add these items to the To-Do list (I”ll check that technical issue later). I quickly responded with the yellow highlighted note on the Home page you see below, but I still was getting apology messages for missing work they couldn’t tell they needed to do.

This morrning a student wrote me saying she was sorry she missed it, but the primary source assignment wasn’t on the To-Do list. I sent a student my screenshot in Student View, showing that the assignment was indeed appearing on the list.

She replied with two screenshots where it wasn’t there. Here’s the one she sent from her phone:

And it suddenly hit me. The process she’s accessing, the To-Do List, lists all the tasks for all the classes a student takes. It thus disaggregates the courses entirely. She’s no longer taking my History class, or a Sociology class. She’s just doing work, clicking links, crossing things off a list.

By showing the student the tasks for the day, for all three of her classes, Canvas has not only reasserted its contention that all learning tasks are equivalent, but that they are tasks unrelated to anything else. They are just stuff the student needs to complete.

Most scholars think in terms of their field, then teachers think in terms of wrapping elements together to encourage understanding. On my weekly page, you can see that the tasks for the week relate to each other. They are all part of that week’s topic. They follow sequentially: first post the primary source (forum), then check it for points (quiz). My design has instantly become irrelevant.

My practical response today has been to go through all my classes, adding the weekly page to the To-Do list, as the first thing that week. It will be tricker to do this for my lectures and other non-graded or linked items, since Canvas doesn’t “see” those at all. I will have to link each on a Page and put the Page on the To-Do list, forcing students to click twice to get to it. This will take all weekend.

But my holistic response is much more important. The units we teach are no longer units — they contain no flow or contiguity when seen as disparate tasks. If students access all academic work as a flat list of tasks, there is no connection between assignments. There is no connection, for example, between Reading 3 and Quiz 3. Assign the Reading for Monday. Assign the Reading Quiz for Wednesday, and it isn’t clear they relate to each other.

This explains the other messages I’m receiving. “I see we have a Lecture quiz due, but what is that on?” At first I smirked and thought, “The Lecture, of course!” But now I realize they don’t see the Lecture unless they’re on the weekly page. “The Calendar says the second post is due – where do I post?” You can’t put two due dates for the same discussion forum. They don’t know where to return to in order to post.

In an age when we worry that students don’t read whole books, we have something here that is much worse. How can they do sequential and scaffolded learning when the system won’t let you scaffold?

It changes the rules utterly. Here are the “new” rules (some have been good practice for awhile):

1. Assessment and responses must appear with the content.

Quiz 3, in other words, must contain Reading 3 within it. You can’t have a link for Reading 3 on Monday and Quiz 3 on Wednesday.

Note here that group text annotation, of the kind I’m using in Perusall, is ideal. The content and the activity are inextricably linked.

2. Double-level discussion may not work.

In Canvas, to have students return to a discussion, it will be necessary to link to that same discussion in the Calendar later in the week.

One alternative will be to have the entire class inside a discussion forum. This won’t work in Canvas because it doesn’t allow real threads, but might work in other systems.

3. Navigation schemes are useless.

Obviously, my own weekly page navigation, even if it’s on the To-Do list, is worked against forcefully by Canvas.

Some would say return to Modules. But Canvas’ own Modules are irrelevant, except for adaptive release, or to force task order. Students won’t use the Modules page either, even if it’s the main page. They may never see it.

This also applies to the Home page itself, especially a nice one. It is now obsolete. All we’ve learned about making the Home page welcoming is irrelevant.

Again, the new rules (and I’m sure there will be more as we all think about it) are the result of the disaggregation of content and tasks. This is both an effect of the technology, and a cause of the disaggregation of knowledge. We’d better plan accordingly.

All the books I’ve used, including works by

All the books I’ve used, including works by

Most instructors have a discussion forum. Some of these are problematic or meaningless, but if they do it every week, they’re good. I can justify much of my students’ work, because in addition to annotating written primary sources, they post their visual sources in a forum, and “like” the sources they enjoy. “Like” is interaction, and if you ask students to “like” for a purpose (they plan to use the idea, or vote up ideas the class will use), it’s meaningful.

Most instructors have a discussion forum. Some of these are problematic or meaningless, but if they do it every week, they’re good. I can justify much of my students’ work, because in addition to annotating written primary sources, they post their visual sources in a forum, and “like” the sources they enjoy. “Like” is interaction, and if you ask students to “like” for a purpose (they plan to use the idea, or vote up ideas the class will use), it’s meaningful.