This semester I have begun using Kami (previously Notable PDF) so that my students can annotate scholarly articles I’ve uploaded in pdf. This has worked well. But Kami has ads (yucky Google-style sidebar crap), so I’ve just asked my department to purchase the $50 upgrade to remove them.

In the process of realizing payment was required to prevent Kami ads telling me and my students about the “early signs of a heart attack!”, I took a second (third?) look at Hypothes.is, a service with more of an educational/edupunk attitude.

Some distinctions follow. (Keep in mind that Kami is just for pdfs, while Hypothes.is also does web pages. There are many tools that allow you to annotate web pages by adding a layer. Crocodoc, which I used to use happily, is gone. Many other annotation plugins that are for private, browser-based use. And Diigo is just more than I need.)

Appearance

Kami has bigger font and is better on phones and mobile devices. It’s showier, with lots of big buttons for the features, and you can have your photo showing next to your posts. PDF rendering is a bit better in Kami.

Hypothes.is fits better on the page and its annotation panel retracts. The toolbar creates wiki-like coding which is awkward – even bold and italics look funny in draft mode.

However, in Kami, though you can write and draw on the pdf, there is no formatting at all available in the annotations. How can I make a point without italics?

Cost

Kami, as noted, has ads or you pay. Hypothes.is is free.

Support

Both seem to have good support. Within minutes setting up my free account, and then again when I paid, Kami contacted me. Within minutes of creating a group in Hypothes.is, they contacted me.

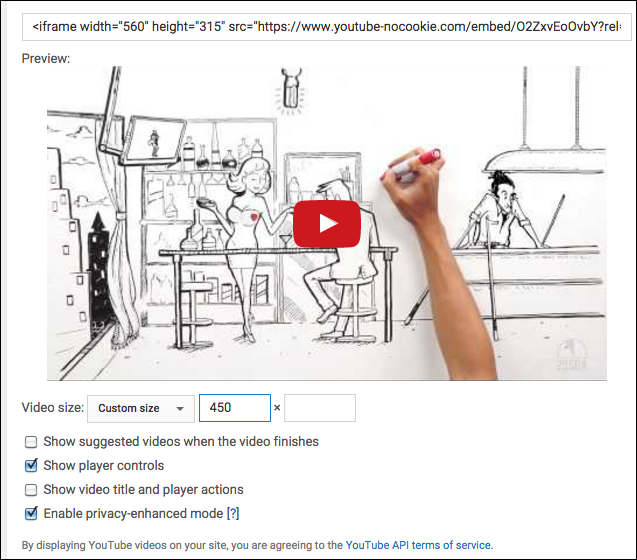

Embedding in an LMS page

Kami works in an iframe in Moodle. Hypothes.is doesn’t seem to. Kami works using the Redirect tool in Canvas. Hypothes.is, despite the https designation in via, forces a new tab in Canvas. (Sorry, I don’t have gloves on so I didn’t touch Blackboard.)

Tracking students

Neither system (nor any annotation app, to my knowledge) works with LTI or inside the LMS, so I have to track manually. Kami allows me to upload pdfs of the articles right into their system, then any student with a Kami account can have their name on their annotation. For students who post as a “guest” I request that they sign their annotations so I know who posted. I have to remind them. Hypothes.is lets you see public annotations on the page, but you must have an account to annotate, so there will be no “guests” to track.

How annotations work

In Hypothes.is, the annotation area appears as a slide-out panel. It automatically posts any highlighted text in the annotation box, and allows for nested replies, which could generate true discussion. In Kami, the annotation panel takes up some real estate on the right of the screen, with the document zoomed out on the left (you can zoom in). Replies have a grey background and are attached below the original annotation post, but are not nested.

In Hypothes.is, the “via” proxy feature allows me to make any web page available for annotation just by adding https://via.hypothes.is/ to the front of the URL. So I thought I’d try Hypothes.is on the open textbook I just adopted, The American Yawp. If you sign in with Hypothes.is, you’ll see that the page (I looked at Chapter 8) has already been annotated, obviously by other students. You can see it without an account at https://via.hypothes.is/www.americanyawp.com/text/08-the-market-revolution/.

But I can create a “group” for just my class, and everyone must use the drop down at the top of the annotation entry box to select the group name. This limits the page to just those in the group, both viewing and making annotations. Kami doesn’t need groups since the URL of my uploaded file is only shared with my students.

In Hypothes.is, I can also upload a pdf of the chapter, and put https://via.hypothes.is/ in front of it, and have a fresh (OCR, not quite as clear, but totally workable) copy only my students can work with. This also means that any pdf I upload will work, and it can still be hosted on my server, although the annotations are hosted at Hypothes.is.

Coding my own webpages

In Hypothes.is, for my own webpages, I can add the code into the page like this:

https://hypothes.is/embed.js

https://hypothes.is/embed.js

The annotation panel then appears on the page. This is good for my primary sources, which are all in HTML anyway. I also can make web pages with pictures from the open text, and we can discuss them. There is no such feature with Kami.

Privacy and copyright

In Hypothes.is, at the bottom of the annotation entry window it shows the Creative Commons license as Public Domain, meaning

“You can copy, modify, distribute and perform the work, even for commercial purposes, all without asking permission.”

I do not use this cc designation on my own work – I use NC (non-commercial) and SA (share alike). I am uncomfortable with the idea that others could use things I and my students write, and sell them. However, on the Hypothes.is FAQ it says:

Annotations made privately or in a group are the property of the individual user (“All rights reserved”) and are ?not? in the public domain or licensed under Creative Commons.

If I make a group, things are more private so long as everyone remembers to use the drop down for the group So I figure I’ll use groups for Hypothes.is. I do not know who “owns” Kami’s annotations, but I have inquired.

Mobile

Although Jeremy Dean of Hypothes.is indicated to me that it wasn’t yet completely mobile-friendly, on my phone Hypothes.is worked much better than Kami.

So I’m sticking with Kami for this semester (even in a History of Technology class there’s a limit how many things you can ask students to sign up for). But Hypothes.is’s flexibility, nesting, and server-side Javascript makes it a serious contender for next year, though the iframe incompatibility is a definite issue.

The implication is that any depth must exist within the instructional materials accessed through the system. At the top level, the environment in which the student must work, the danger of cognitive overload is mitigated by providing as few options as possible. It is a clear return to 4th grade “computerized learning”, the kind that takes place in a lab. Pupils sit at stations, and the software guides them step-by-step by pressing as few buttons as possible. With visual and touch-screen interfaces, this is now even easier. Complete a small task, get instant feedback, press ‘Next’.

The implication is that any depth must exist within the instructional materials accessed through the system. At the top level, the environment in which the student must work, the danger of cognitive overload is mitigated by providing as few options as possible. It is a clear return to 4th grade “computerized learning”, the kind that takes place in a lab. Pupils sit at stations, and the software guides them step-by-step by pressing as few buttons as possible. With visual and touch-screen interfaces, this is now even easier. Complete a small task, get instant feedback, press ‘Next’. Although at first there had been plans to teach information literacy as a school requirement, this trend has tapered off because of such ease of use. In many places, information literacy is still articulated as a goal, but is not implemented in any meaningful way. The result has been students who have no idea what to type into Google when asked to find, for example, information about American imperialism in the late 19th century. We already are aware of the challenges of distinguishing between good and bad sources of information, and want students to distinguish between a scholarly source and a pop culture source. But instead of increasing skills, the fear of bad websites has led to banning certain things, through filters in grade schools and syllabus dictates in college. (When I encouraged my student to use Wikipedia to find primary sources, she was aghast, telling me it had been drilled into her head for years never to use Wikipedia for school.)

Although at first there had been plans to teach information literacy as a school requirement, this trend has tapered off because of such ease of use. In many places, information literacy is still articulated as a goal, but is not implemented in any meaningful way. The result has been students who have no idea what to type into Google when asked to find, for example, information about American imperialism in the late 19th century. We already are aware of the challenges of distinguishing between good and bad sources of information, and want students to distinguish between a scholarly source and a pop culture source. But instead of increasing skills, the fear of bad websites has led to banning certain things, through filters in grade schools and syllabus dictates in college. (When I encouraged my student to use Wikipedia to find primary sources, she was aghast, telling me it had been drilled into her head for years never to use Wikipedia for school.)

The second idea was the way Jim makes students read each others’ work. Not only does he refer to student posts in his own comments, but he has quizzes where the student must match the post author with an idea from that author’s post.

The second idea was the way Jim makes students read each others’ work. Not only does he refer to student posts in his own comments, but he has quizzes where the student must match the post author with an idea from that author’s post. But that’s not the real challenge – it’s the material. For each chapter, there is a long list of resources: document activities, image activities, map activities, “closer look” features. Since each of these has at least one question attached (I assume that’s the “activity” – there’s nothing else active here), I assumed these were multiple choice questions, for automatic grading. Turns out most of them are “essay” questions, all of low quality (i.e. “what is x talking about in this document?”), that I would have to grade. I’ve assigned over a dozen for each chapter. Besides, the whole idea of the experiment was to be using their pedagogy as much as possible instead of mine.

But that’s not the real challenge – it’s the material. For each chapter, there is a long list of resources: document activities, image activities, map activities, “closer look” features. Since each of these has at least one question attached (I assume that’s the “activity” – there’s nothing else active here), I assumed these were multiple choice questions, for automatic grading. Turns out most of them are “essay” questions, all of low quality (i.e. “what is x talking about in this document?”), that I would have to grade. I’ve assigned over a dozen for each chapter. Besides, the whole idea of the experiment was to be using their pedagogy as much as possible instead of mine. Some don’t even have a date! They let you into just enough code that I can kind of correct some of these by adding words to the title. But there are audio files with no lyrics or transcripts. And, worst of all, the primary source video clips (Edison’s footage of Annie Oakley, footage of the Rough Riders) are in low resolution and look terrible. I could find better quality of the same footage using Internet Archive. There are also typographical errors in the transcript and in the titles and descriptions of the sources.

Some don’t even have a date! They let you into just enough code that I can kind of correct some of these by adding words to the title. But there are audio files with no lyrics or transcripts. And, worst of all, the primary source video clips (Edison’s footage of Annie Oakley, footage of the Rough Riders) are in low resolution and look terrible. I could find better quality of the same footage using Internet Archive. There are also typographical errors in the transcript and in the titles and descriptions of the sources. As I continue to advocate hand-made “artisan” online classes and openness and freedom, all forces are moving in the other direction. New education initiatives lead us into forced, system-wide learning management systems, standardized rubrics for evaluating what makes a “good” online class, and tracking mechanisms that give surveillance a whole new meaning.

As I continue to advocate hand-made “artisan” online classes and openness and freedom, all forces are moving in the other direction. New education initiatives lead us into forced, system-wide learning management systems, standardized rubrics for evaluating what makes a “good” online class, and tracking mechanisms that give surveillance a whole new meaning.

I’ll use Blackboard as the LMS. I’ve linked the Pearson MyHistoryLab account to the Blackboard course. Although this was supposted to provide “integration”, what it provided was essentially a button that links the student out to the Pearson MyHistoryLab website. Frankly, I was expecting something a little more sophisticated. I know that several of my colleagues use course packages that are more seamless, but I guess History isn’t one of the hot sellers for this stuff.

I’ll use Blackboard as the LMS. I’ve linked the Pearson MyHistoryLab account to the Blackboard course. Although this was supposted to provide “integration”, what it provided was essentially a button that links the student out to the Pearson MyHistoryLab website. Frankly, I was expecting something a little more sophisticated. I know that several of my colleagues use course packages that are more seamless, but I guess History isn’t one of the hot sellers for this stuff. An introductory video about me containing some personal revelations

An introductory video about me containing some personal revelations I call this the Jekyll and Hyde Experiment because it feels like I am two different instructors. Jekyll teaches “old-fashioned”, hand-made classes designed to provide students with choices and freedom within a structure. Hyde will teach with materials and assessments developed and sold by someone else.

I call this the Jekyll and Hyde Experiment because it feels like I am two different instructors. Jekyll teaches “old-fashioned”, hand-made classes designed to provide students with choices and freedom within a structure. Hyde will teach with materials and assessments developed and sold by someone else.