More session reports! (I know, you’ve been waiting — but I do this so I remember the sessions.)

Petitioning and the Politics of Nation, Gender, and Empire shows the problems with titling panels, as it was really more about the process of petititoning the government, not so much politics or any of the sub-factors.

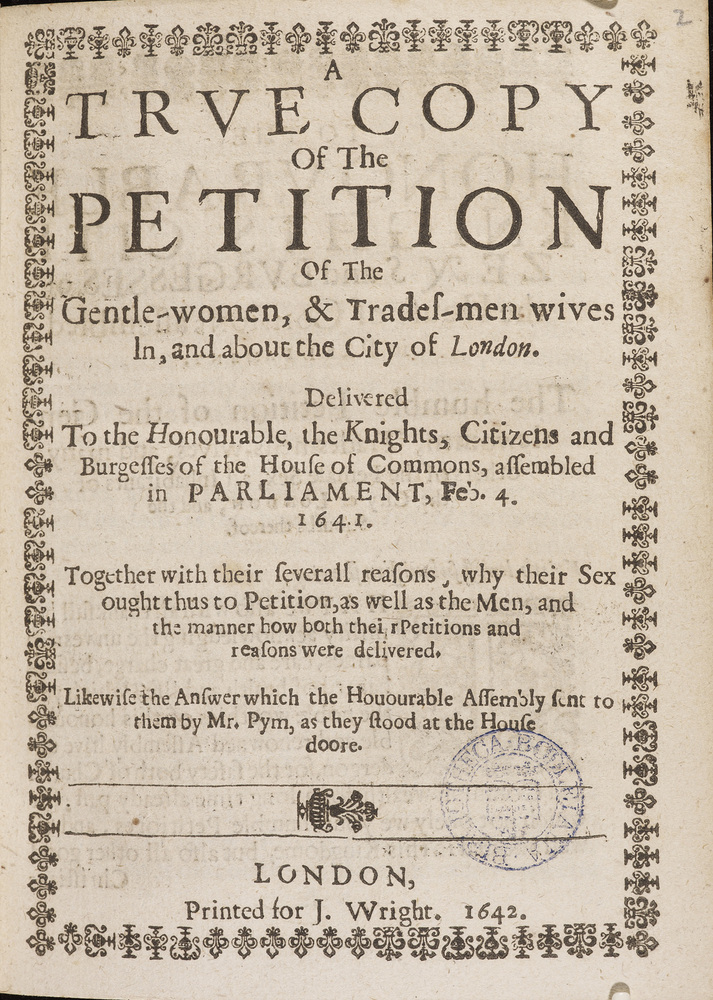

Laura Stewart’s “Petitioning Practices in Early Modern Scotland” looked at how political petitioning (petitioning in order to criticize the government) and ordinary supplications interact, in this case as regards the Covenanter government of Scotland in the 1640s, an era surrounding the English Civil War. Although it’s hard to quantify the total number of petitions, case studies provide a variety of significances, including whether a petition can be considered libel, what language supplicants used in their petitions, and how government critiques can provide a foundation for a petition.

Richard Huzzy and Henry Miller’s “The Rise and Fall of Petitions to the House of Commons, 1780-1918” was a good example of the kind of research you can do with a grant, in this case from the Leverhulme Trust. They were able to sort and recategorize thousands of petitions and numbers of signatures. Between 1833 and 1918 Parliament received 950,000 public petitions on 29,500 different issues, and their charts showed spikes in certain years. The categories included colonies, ecclesiastic, economic, infrastructure, legal, social, taxes, war. They had broken down colonies but I was sad to see that “education” wasn’t its own category, as that might have been helpful for my work. They noted certain politically organized pushes for petitions, which were clearly used to mobilize support on certain issues.

Ciara Stewart’s “Petitioning against the Contagious Diseases Acts in Britain and Ireland: A Comparative Perspective” helped me understand the foundational idea of many papers. It’s important to narrow the focus to a single argument with depth of sources. To me, petitioning against the CDA would have been its own paper, but it’s clear now that I’ve attended the conference that this is not the best way. By focusing closely on the Ladies National Association in Ireland and its composition, then comparing it favorably to the English LNA, Stewart was able to prove that the Irish branch should be taken more seriously. The paper avoided the usual discussion of whether the CDA was a good idea or not, though it did mention the reasons for supporting petitioning against it: the double standard it promoted by not examining men, the fact that the examinations were forced, and the arguments about the likelihood of police grabbing women to examine even if they had committed no crime (“protect your wife and daughters”). Previous historiography had sidelined the Irish LNA, and I recalled that the purpose of most papers is to oppose previous historiography. I tell students that this is an “although” thesis (“although we’ve been told that the Irish LNA was just a side branch, it was actually significant”).

In my case, then, an example might be “although the focus of historical study for higher education in the Victorian age has been on universities, extension courses, and the examination system itself, correspondence courses for degree exams were a significant means of advancing education among the lower middle classes…”

The session I was looking forward to the most was next: The Educational Institution as a Category of Analysis in Modern British History. The chair, Peter Mandler, noted that education has been a missing element, long neglected in British social history, although it is well-served now. Emily Rutherford’s “Opposition to Coeducation in British Universities 1880-1939” had a thesis that I would summarize as “although the historical focus of gender in universities is based on women trying to gain access to higher education, there are important elements in resistance to it, particularly personal comfort levels and administrative constraints”, including the role of donors. The wishes of donors (she cited donors who wanted to support single-sex institutions) could be at odds with the wishes of administrations. In some cases, like that of Queen Margaret College at the University of Glasgow, it was wasteful to teach women-only classes, and the argument was made that biases against women would mean lower marks for them than if their exams were mixed with men’s. (Later in the Q&A a concern was raised about the cost to working-class boys of middle-class girls dominating classes.) The speaker also introduced the interesting case of Edward Perry Warren, an art collector and scholar of the idealized male Greek life cycle of homosexuality, who funded a male lectureship on the condition that the lecturer live at the college and there be a passage between his house and the boys’ lodgings.

Laura Carter’s “Locating Self and Experience in the History of Secondary Education in the UK: The View from 1968” discussed a project that followed baby boomers and their perceptions about their education into adulthood, and meant to extract education from the history of social change. Many of the students, as adults, regretted missing opportunities while they were in school, but none regretted attending a modern secondary school. Although when asked about moving up socially, those from manual worker families cited money and luck as primary factors, and non-manual labor families cited education, all named education as the key to self-improvement. Also interesting was that among those who didn’t go to university, men cited external reasons (like jobs), while women cited family responsibilities which prevented them.

William White’s “‘A Symbol of all this University Doesn’t Stand for’? The Place of Religion in Post-war University Life” had an implied thesis, of course: “although historians cite the removal of religion from student life during the 1960s, conflicts over chapels and religious buildings on campus show much student interest in Christianity”. We should be asking why new chapels were being built all over if religion was in a downturn. White wisely printed out his slides, rather than projecting them, to demonstrate the modernist architecture to which many students objected on aesthetic grounds. He also noted that the student body was changing in the 1960s from more local attendance to students who were more mobile, national in their perspective, and residential since they came from elsewhere. Thus residence halls were another architectural feature of the era. The new welfare state was, in effect, taking over from local churches, with chaplains in the NHS and religious programming on the BBC. Christianity saw a resurgence after the war, and there was an ecumenical movement.

Commentator Laura Tisdall noted that we need to take school out of the “history of education”. The history of education is not seen a real history, and needs to be integrated into modern history. It’s been neglected, she said, because the subject is embedded in teaching training colleges and departments of Education rather than History, that there’s a sense that we know it already since we’ve all been to school, and that it is associated mostly with the history of childhood (which has seen a proper resurgence). University history is even more neglected, and further education is positively marginalized. So although I enjoyed the papers, the commentary was even more important in sorting out where my work fits in History as a discipline. I have struggled with History of Education societies, which seem to be composed of educators who dabble in history. What I’m doing, as I’ve mentioned, is more traditional history — education just happens to be the subject.

The last session I attended (other than my own) was just for fun: Aspiring Writer and Aristocrats: Renegotiations of Elite and Mass Cultures, 1890-1940. Abigail Sage’s “Print Media and the Aspiring Writer in the Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries” examined periodicals like Young Man and Young Woman which encouraged potential fiction writers with advice columns. She even quoted HG Wells as saying he was part of a whole generation of aspiring writers. Mo Moulton’s “Murder Mysteries, Socialist-Utopian Science Fiction, and the Mediation of Elite and Popular Cultures in the 1920s-1930s” looked at Dorothy L. Sayers and Muriel Yeager as representative of conservative modernity, both reflecting pessimism about human nature. I learned a lot about the character of Lord Peter Wimsey (whom I’ve seen on TV but never read), and about Yeager’s relationship with Sayers, and about Sayers’ interest in Christianity. Wells was mentioned here too, as a utopian author, with Yeager saying she opposed his views, but certainly The Time Machine is as dystopian as anything she wrote, so she must have meant his later work on socialism. I am, however, beginning to wonder whether one can present a paper on writing during the 1890s without mentioning Wells!

The very last session (last session, last day, and I was the last speaker) was the one I was in: Popular Culture and Popular Education in Victorian England. Anne Rodrick’s “‘Lectures Both Scientific and Literary’: Organizing Mid-19th-Century Lecture Culture” discussed the General Union of Literary, Scientific, and Mechanic’s’ Institutes and how they debated the best ways to provide lectures to the public. She compared their efforts unfavorably to the American Lyceum system, and showed how particularism and provincial concerns prevented a well-organized lecture culture. Martin Hewitt’s “Providing Science for the People: The Gilchrist Turst 1878-1914” explored how the Trust developed and promoted popular science lectures, and also noted some problems with development. While the lectures were highly successful due to their high quality, low ticket price, friendly connections with local authorities, and massive advertising campaigns (even door-to-door) to get people to attend, in the long run it was difficult to sustain. There was also some question as to how many attendees were actual rural or manual laborers, and complaints that the low cost made it difficult for other lectures to get an audience. My own paper, “‘Preposterous and Necessary’: H.G. Wells, William Briggs, and the University Correspondence College” focused on the development of the UCC as a viable method for lower-middle-class people to study for the University of London examinations and earn their degrees. I argued that distance education like that offered by the UCC was essential to the success of the examination system, although I need to work further on that approach. I was asked no questions, and got the sense that my paper was too broad, more like a class lecture rather than a research report (I had, in fact, written it for presentation rather than publication). I made slides but there was no adapter for my iBook to connect to HDMI, and tech support didn’t show, so I was glad I’d made sure my visuals were illustrative rather than essential. I came out feeling I have a great deal of work to do to get close to the quality of the other papers I saw, but that’s a good reason for going, yes?